- Français

- |

- Booklist

- |

- Week of Prayer

- |

- Links

- Areopagus - a forum for dialogue

- Academic journals

- Acronyms

- Bible tools

- Bibliographies

- Booksellers and publishers

- Churches

- Canadian church headquarters

- Directory of Saskatchewan churches

- Retreat centres

- Saskatchewan church and non-profit agencies

- Ecumenism.net Denominational links

- Anabaptist & Mennonite

- Anglican

- Baptist

- Evangelical

- Independent episcopal

- Lutheran

- Methodist, Wesleyan, and Holiness

- Miscellaneous

- Mormon

- Orthodox (Eastern & Oriental)

- Para-church ministries

- Pentecostal / charismatic

- Presbyterian & Reformed

- Quaker (Society of Friends)

- Roman & Eastern Catholic

- United and uniting

- Documents of Ecumenical Interest

- Ecumenical agencies

- Ecumenical Booklist

- Ecumenical Dialogues

- Glossary

- Human rights

- Inter-religious links

- Justice & peace

- Lectionaries

- Religious news services

- Resource pages

- Search Ecumenism.Net

- |

- Documents

- Ancient & Medieval texts

- Ecumenical Dialogues

- Interreligious

- Anabaptist & Mennonite

- Anglican

- Evangelical

- Lutheran

- Orthodox

- Reformed & Presbyterian

- Roman & Eastern Catholic

- United & Uniting

- Miscellaneous churches

- Canadian Council of Churches (CCC)

- Conference of European Churches (CEC)

- Interchurch Families International Network (IFIN)

- National Council of Churches in Australia (NCCA)

- Lausanne Committee for World Evangelism (LCWE)

- World Council of Churches (WCC)

- Other ecumenical documents

Church traditions

Documents from ecumenical agencies

- |

- Dialogues

- Adventist-Reformed

- African Instituted Churches-Reformed

- Anglican-Lutheran

- Anglican-Orthodox

- Anglican-Reformed

- Anglican-Roman Catholic

- Anglican-United/Uniting

- Baptist-Reformed

- Disciples of Christ-Reformed

- Disciples of Christ-Roman Catholic

- Evangelical-Roman Catholic

- Lutheran-Mennonite

- Lutheran-Mennonite-Roman Catholic

- Lutheran-Reformed

- Lutheran-Roman Catholic

- Mennonite-Reformed

- Mennonite-Roman Catholic

- Methodist-Reformed

- Methodist-Roman Catholic

- Oriental Orthodox-Reformed

- Orthodox-Reformed

- Orthodox-Roman Catholic

- Pentecostal-Reformed

- Prague Consultations

- REC-WARC Consultations

- Roman Catholic-Lutheran-Reformed

- Roman Catholic-Reformed

- Roman Catholic-United Church of Canada

- |

- Quick links

- Canadian Centre for Ecumenism

- Canadian Council of Churches

- Ecumenical Shared Ministries

- Ecumenism in Canada

- Interchurch Families International Network

- International Anglican-Roman Catholic Commission for Unity and Mission

- Kairos: Canadian Ecumenical Justice Initiatives

- North American Academy of Ecumenists

- Prairie Centre for Ecumenism

- Réseau œcuménique justice et paix

- Week of Prayer for Christian Unity

- Women's Interchurch Council of Canada

- World Council of Churches

- |

- Archives

- |

- About us

Vatican II’s Nostra Aetate and Christological Understanding

Vatican II’s Declaration Nostra Aetate does not delve into Christological understanding in a direct way. But through its affirmations of continued covenantal inclusion on the part of Jews and Judaism, it undercuts a central base for classical Christianity. How can the restored covenantal inclusion for Jews be proclaimed side-by-side with the longstanding belief in Christ’s salvific work?

…

In recent years we have witnessed a movement in scholarly circles to reorient the image of Paul. That effort has led to a focus on the compatibility of Pauline teaching with the tenets of Second Temple Judaism. Hence, any Christology rooted simplistically in a “law-gospel” or “flesh-spirit” dichotomy can no longer stand the test of scholarly inquiry relative to Paul. While the new scholarship may present Pauline teachings on the significance of Jesus the Christ with different shadings, there is a building consensus that earlier portrayals of Paul’s vision in this regard have seriously distorted his intent.

Read the complete article in JCRelations.net from the International Council of Christians and Jews

Permanent link: ecumenism.net/?p=14658

Permanent link: ecumenism.net/?p=14658

Categories: Opinion • In this article: Jewish-Christian relations, Judaism, Nostra Aetate, Second Vatican Council

Lien permanente : ecumenism.net/?p=14658

Lien permanente : ecumenism.net/?p=14658

Catégorie : Opinion • Dans cet article : Jewish-Christian relations, Judaism, Nostra Aetate, Second Vatican Council

We believe! The Nicene Creed and Christian Unity | One Body

— Oct. 3, 20253 oct. 2025

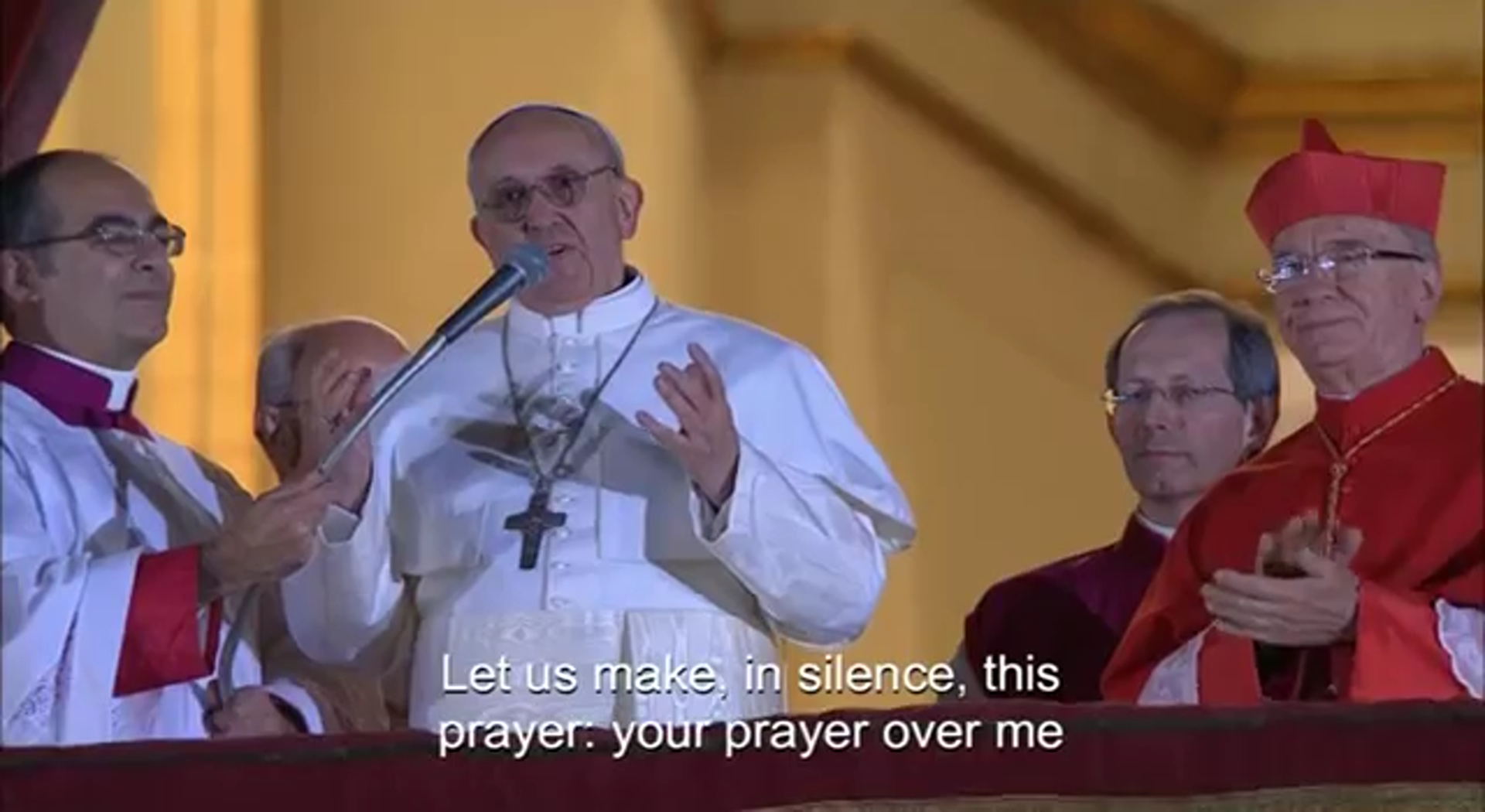

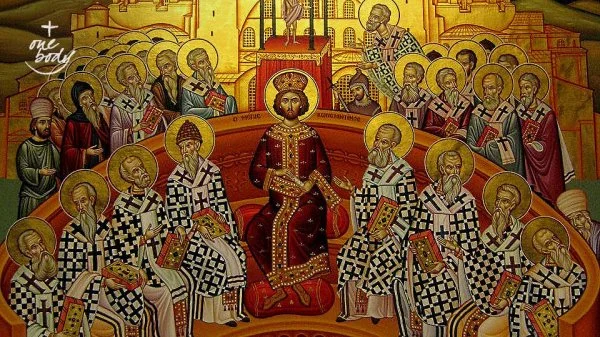

“We believe.” These are the first words of the original Nicene Creed, written 1,700 years ago at the Council of Nicaea. This ecumenical council in 325 AD produced a summary statement of Christian belief that has been professed by Christians around the world ever since. Both for its longevity and its universal appeal, the Nicene Creed stands apart from every other statement of Christian belief. It also has a profound ecumenical significance, which I explored in January’s One Body article, Do You Believe This?

At the end of November, Pope Leo XIV is expected to visit Nicaea with Orthodox Patriarch Bartholomew. Each year, the pope and patriarch send delegations to the other to celebrate their patronal feasts of Sts. Peter and Paul in Rome on June 29 and St. Andrew in Constantinople (Istanbul) on November 30. This year, in the modern city of Iznik, where Nicaea once was, the two leaders will together commemorate the 1,700th anniversary of the first ecumenical council. They will also commend the church to continue in the dialogue of life and love begun at the end of the Second Vatican Council.

… Read more » … lire la suite »

Spotlight on Catholic-Mennonite Dialogue | One Body

— Aug. 28, 202528 aoüt 2025

A number of years ago, at a local dialogue meeting of Catholics and Mennonites in Edmonton, we considered together that section of the Catechism of the Catholic Church that pertains specifically to the “one-ness” of the Church (#811-822).

I remember in particular a great discussion that ensued around CCC #815. It delineates the “bonds of communion” which, for Catholics, mark and hold Christians in unity with one another within the Body of Christ. That paragraph reads:

What are these bonds of unity? Above all, charity “binds everything together in perfect harmony.” But the unity of the pilgrim Church is also assured by visible bonds of communion:

- profession of one faith received from the Apostles;

- common celebration of divine worship, especially the sacraments;

- apostolic succession through the sacrament of Holy Orders, maintaining the fraternal concord of God’s family.

Roman Catholic–United Church (RC-UC) Dialogue | One Body

— July 15, 202515 juil. 2025

This year, 2025, marks the 100th anniversary of the founding of The United Church of Canada (UCC). It is a uniquely Canadian church, formed in part in response to the desire to minister effectively to the many small Christian communities scattered across the sparsely populated prairie provinces. The UCC has been committed to the search for Christian unity from the time of its foundation, something it has clearly expressed in its fifty year dialogue with the Canadian Roman Catholic Church.

Following an exchange of correspondence between the UCC General Council and the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops (CCCB) in the fall of 1974, the Roman Catholic/United Church Dialogue held its first meeting in November 1975. Appointed by the UCC’s Inter-Church and Inter-Faith Relations Committee and the CCCB’s Episcopal Commission for Ecumenism, dialogue participants are committed to improving relationships between the two churches, and to countering misinformation, stereotypes, and prejudices. It explores pastoral, theological, and ethical issues, including those that have traditionally prevented full unity. In consultation with its two sponsoring bodies, the group determines its agenda, reports periodically on the dialogue and seeks ways of communicating what it has learned from the dialogue.

… Read more » … lire la suite »

Preparatory meeting convenes in lead-up to WCC Sixth World Conference on Faith and Order

— July 1, 20251 juil. 2025

A planning meeting for the World Council of Churches (WCC) Sixth World Conference on Faith and Order and the Global Ecumenical Theological Institute 2025 (GETI) was convened in St Bishoy Monastery in Egypt, 28-29 June. The hybrid gathering focused on logistics, a stewards programme, communications, church and cultural visits, and budget.

The cohost for the conference is the Coptic Orthodox Church, marking the first time such a conference is hosted by an Oriental Orthodox church.

The Sixth World Conference for Faith and Order, being hosted at the invitation of His Holiness Pope Tawadros II, will be held in Wadi El Natrun, Egypt, from 24-28 October with the theme “Where now for visible unity?”

This will be the sixth such conference in a century, with previous gatherings held in 1927 (Lausanne, Switzerland), 1937 (Edinburgh, Scotland), 1952 (Lund, Sweden), 1963 (Montreal, Canada),1993 (Santiago, Spain) and 2025 (Wadi El Natrun, Egypt).

… Read more » … lire la suite »

Bishop Shane Parker elected 15th Primate of the Anglican Church of Canada

— June 26, 202526 juin 2025

The Rt. Rev. Shane Parker, Bishop of Ottawa, was elected the 15th Primate of the Anglican Church of Canada on June 26, 2025, at St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, Ontario, during the 44th session of the General Synod.

Primate-elect Parker has served as the Bishop of the Anglican Diocese of Ottawa since 2020. Prior to that, he was dean of the Diocese of Ottawa and rector of Christ Church Cathedral in Ottawa for two decades. He has a master’s degree in sociology from Carleton University, as well as an honorary doctorate from Saint Paul University, where he has served as a part-time professor of pastoral ministry and chairs its Anglican Studies Advisory Committee.

… Read more » … lire la suite »

Joe Elkerton appointed Director of Indigenous Christian Fellowship

— June 25, 202525 juin 2025

The Christian Reformed Church’s Indigenous Christian Fellowship (ICF) in Regina, Sask., is pleased to announce the appointment of Joe Elkerton as its new director, effective July 21, 2025. Elkerton will replace Bert Adema, who is retiring after 32 years of service.

“This appointment marks a pivotal moment for the Indigenous Christian Fellowship,” said Albert Postma, the CRCNA’s executive director-Canada. “Joe’s diverse background and his clear sense of calling to this specific role truly excite us. We believe his leadership will bring vibrant new energy and direction as we continue to grow and serve the community in Regina.”

… Read more » … lire la suite »

WCC supports efforts to reform and strengthen United Nations

— June 24, 202524 juin 2025

In a statement, the World Council of Churches (WCC) central committee commemorated 80 years of the United Nations, particularly its founding principle of multilateral cooperation.

“The Pact for the Future, adopted by the UN General Assembly in September 2024, lays out some important directions and needed reforms,” notes the statement. “But even deeper and more fundamental reform will be required, including of the Security Council itself, in order to restore the organization’s credibility and to address the historic exclusion of nations still under colonial domination at the time of the 1945 San Francisco Conference.”

… Read more » … lire la suite »

“The courage to love,” the miracle of ecumenical reconciliation

— June 20, 202520 juin 2025

Long-time Bridgefolk participants remember the booming voice of the late Ivan Kauffman celebrating historic moments that have marked the development of closer relationships between Mennonites, Roman Catholics, and other divided Christians: “It’s a miracle!”

Kauffman would almost shout it. But he had a solidly empirical definition for miracles to match his exuberance: “Things that everybody agreed could not happen, but that happened anyway.”

If Kauffman could have been in Zurich, Switzerland on 29 May 2025, we would surely have heard his booming voice again. Commemorating the 500th anniversary of the Anabaptist movement that began in January of 1525, its spiritual descendants in Mennonite, Amish, Hutterite, and related churches gathered at the city’s Grossmünster cathedral there at the invitation of Mennonite World Conference (MWC).

… Read more » … lire la suite »

Theological schools hit by international student rules intended for diploma mills, larger institutions

— June 12, 202512 juin 2025

Between 2014 and 2024, the proportion of students of European descent at Montreal Diocesan Theological College (often abbreviated as Dio) went from about 60 per cent to 25 per cent, says the Rev. Jesse Zink, the school’s principal.

“We have been moving in a direction that’s much more diverse along lines of immigration status, country of origin, racial, and ethnic identity. And I would just say, I think this is wonderful,” he says. “I was teaching a three-hour class last week. We took a break, and I noticed that students were having little side conversations during our break, and there was one that was happening in English, and there was one that was happening in French, and there was one that was happening in Swahili.”

… Read more » … lire la suite »

Reflecting on a Century of Ecumenical Work and Witness in The United Church of Canada | One Body

— June 7, 20257 juin 2025

June 10, 2025 marks 100 years since 8,000 people gathered in the Mutual Street Arena in Toronto to formally inaugurate, with declarations and worship, The United Church of Canada. Members of the United Church today will easily acknowledge that its history is an ecumenical history, and they remember and celebrate its important contributions to the ongoing search for Christian unity and interfaith cooperation. Reflecting on this history in today’s world of increasingly violent division, fear, and distrust of difference, celebrations also bring questions: what is the continuing ecumenical call to a church committed to “Deep Spirituality, Bold Discipleship, and Daring Justice?”

I offer here a review of that ecumenical history: the beginnings and subsequent life and witness of the United Church, an overview of the church’s ecumenical witness today, and some questions and challenges arising as the church enters the next phase of its life in the world.

… Read more » … lire la suite »